Medieval Warfare picks up where its sister magazine, Ancient Warfare, leaves off. Starting around 500 AD, Medieval Warfare examines the world during the Middle Ages up through the early years of the Renaissance (the magazine generally leaves off in the 16th century). While popular topics such as the Crusades and the Vikings are given regular coverage, Medieval Warfare also tackles more complex and obscure topics, ranging from the Umayyad Caliphate versus the Byzantine Empire to horse trading in 14th-century England.

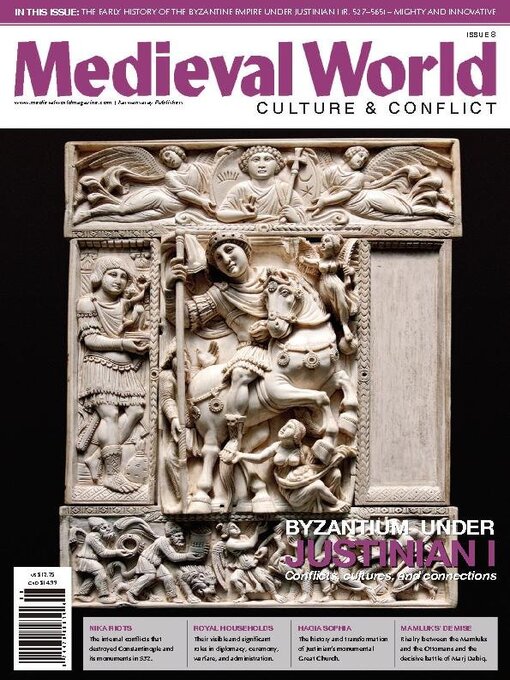

Medieval World Culture & Conflict Magazine

Editorial

New Source for the Norman Conquest

MARGINALIA

Medieval Poland was hit by floods 166 times

ON THE COVER

THE ROYAL HOUSEHOLD • The royal household was among the most vital and complex political institutions within the medieval state. As the most immediate department to the king, it was naturally the primary vehicle for exercising royal authority and supporting the governance of the realm. Therefore, it played a highly visible and undeniably significant role in diplomacy, ceremony, warfare, and administration.

NON-KNIGHTLY HERALDRY • Knights were not the only ones to use heraldry in the Middle Ages. Churchmen, women, and organi- zations had their own heraldry too.

THE BATTLE OF CRECY • The crossing of the Blanchetaque Ford (see MWCC.7) had left the exhausted but exhilarated English astonished at their own good fortune. They escaped the trap that the French had set for them and emerged intact as an army. The Earl of Warwick had engaged in a deadly pursuit of French troops fleeing to Abbeville, while the rest of the army continued toward Noyelles only two miles away. The English stormed Noyelles, looting and burning. Hugh de Despenser took the town of Le Crotoy in a fierce assault. The main force turned east toward the Forest of Crécy.

JUSTINIAN'S BYZANTIUM • It was AD 476 and Rome had fallen. A Germanic-born Roman commander by the name of Flavius Odova- car (ca. 433–493) had dethroned the young emperor Romulus Augustulus (r. 465–476), thus bringing to an end the Roman Empire in the West. Now the torch of what it meant to be Roman shifted to its suc- cessor, which would carry on for over a millennium through the beacon that was the Byzantine Empire.

Justinian's code

PROCOPIUS OF CAESAREA • In late June 533, a vast armada of 500 ships containing 18,000 soldiers, 30,000 sail- ors, weapons, horses, and other supplies lifted anchor at the command of the emper- or Justinian in front of the imperial palace in Constantinople and set sail toward the Mediterranean, ostensibly to ‘liberate’ Vandalic North Africa. On the lead ship, the cam- paign’s commander Belisarius was accompanied by his wife, Antonina, and Proco- pius, the general’s personal secretary (σύμβουλος), who had been appointed in 527.

SEEING BLUE AND GREEN • In the days of ancient Rome, the two main places of entertainment were the Colos- seum and the Circus Maximus; the former for gladiator combat and the latter for char- iot racing. Even after the seat of imperial power moved to Constan- tinople, chariot racing remained a key feature in the lives of Roman citizens. Emperor Constantine renovated the hippodrome in the city in approximately 324. Races consisted of four teams on four-horse chariots racing against each other in a circuit of seven laps, with nor- mally twenty-five races per day.

Where the mob gathers

HAGIA SOPHIA • Ingeniously designed and lavishly endowed with im- ages and objects, the Great Church of Constantino- ple – Hagia Sophia – has enhanced ecclesiastical and imperial ceremonies, awed and inspired, and adapted to changing religious and political circumstances over the course of its long history. A Christian church for almost 1000 years, a mosque for close to 500 years, a museum for 85 years, and now once...

Issue 20 - 2025

Issue 20 - 2025

Issue 19 - 2025

Issue 19 - 2025

Issue 18 - 2025

Issue 18 - 2025

Issue 17 - 2025

Issue 17 - 2025

Issue 16 - 2025

Issue 16 - 2025

Issue 15 - 2024

Issue 15 - 2024

Issue 14 - 2024

Issue 14 - 2024

Issue 13 - 2024

Issue 13 - 2024

Issue 12 - 2024

Issue 12 - 2024

Issue 11 - 2024

Issue 11 - 2024

Issue 10 - 2024

Issue 10 - 2024

Issue 9 - 2023

Issue 9 - 2023

Issue 8 - 2023

Issue 8 - 2023

Issue 7 - 2023

Issue 7 - 2023

Issue 6 - 2023

Issue 6 - 2023

Issue 5 - 2023

Issue 5 - 2023

Issue 4 - 2022

Issue 4 - 2022